A lot of people who fall in love with an incarcerated person have no real understanding of how committing to such a relationship is going to change and affect their lives financially, emotionally, and in many other ways. Reading the new book So You Want to Date (or Marry) a Prisoner?: A Survival Guide for Prison Dating and Marriage by Serena Wilson will help people who are new to such relationships get some insights about the long-term realities. This book even includes a chapter for prison employees and volunteers who find themselves in the forbidden situation of falling in love with a prisoner. It is a short read, but packed with useful information.

Punishing Relations – How WA DOC’s hidden costs and collateral damage imprison families

Washington Corrections Watch has released its first comprehensive report on issues in the Washington Department of Corrections: Punishing Relations – How WA DOC’s hidden costs and collateral damage imprison families.

The devastating effect of decades of mass incarceration on Washington state communities has become increasingly apparent. The financial and emotional burdens of incarceration are primarily borne by female family members of prisoners, most especially in communities of color. Although public dialogue concerning reentry support has increased in Washington, the secondary incarceration of prisoners’ families has not been properly acknowledged. Judicial, legislative, and public deference to Washington Department of Corrections (WA DOC) administrators has precluded proper oversight of WA DOC policies and practices, to the detriment of family relationships and in violation of the legislative intent of corrections (RCW 72.09.010). This is of deep concern, given the crucial role family support during incarceration plays in reducing recidivism. This report documents deficiencies in support for Washington families surviving incarceration, highlighting the needs of both the incarcerated and their loved ones. We identify hidden costs and collateral consequences under WA DOC’s current correctional model and make recommendations for how Washington can better support families surviving incarceration.

The report’s overarching recommendation: We recommend that Washington lawmakers establish an external WA DOC Correctional Policy Oversight Board. Although WA DOC recently created a method for the public to give input on policy revisions, the department is not obligated to use that input. With few exceptions, WA DOC policies are subject only to an internal self-affirming review process when created or revised. Agency WACs also receive less scrutiny than those of other state agencies due to special exceptions in WA DOC’s rule making process. Moreover, WA DOC policy authors and leadership lack the multidisciplinary expertise needed to accurately assess policies for long-term effects on reentry outcomes and recidivism. A multidisciplinary external oversight board comprising legislators, social workers, equity experts, a Statewide Family Council (SFC) representative, a Statewide Reentry Council representative, Disability Rights Washington attorneys, and the Corrections Ombuds, as well as UW Law, Societies, and Justice professors would ensure that WA DOC’s WACs, policies, and Operational Memoranda are thoroughly assessed before implementation for continuous policy improvements that demonstrably lead to superior outcomes in family connections, reentry, and long-term public safety. It would also ensure that WA DOC’s publicized efforts at cultural change and partnerships with the Vera Institute and Amend translate to tangible action in practice.

The report also makes seven additional recommendations and provides a checklist of recommended reforms as an appendix.

Is a One-Size-Fits-All COVID-19 Prevention Protocol Working in Correctional Settings?

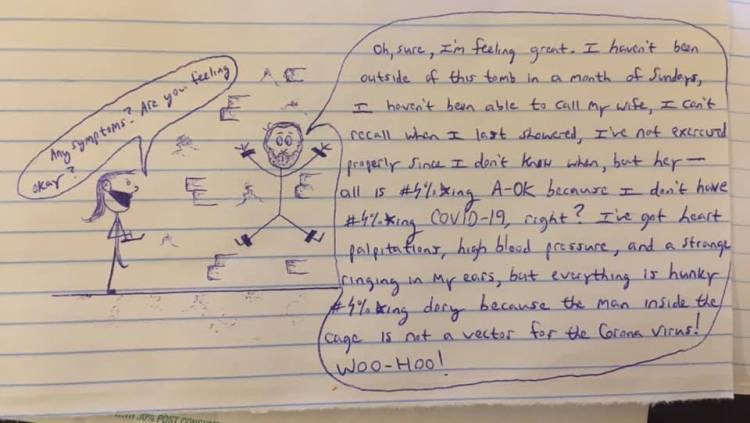

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic mainstream media coverage of how the virus affects prison populations has focused primarily on the rapid spread of the virus and any deaths that have resulted, both among prisoners and staff. There has been less coverage of how individual prisoners and staff members feel about the public health protocols established by the Center for Disease Control and the Washington Department of Health for use in a correctional setting. This post presents the perspective of one 40-year-old prisoner housed at Washington State Penitentiary, which is currently experiencing a large COVID-19 outbreak in several living units. We do not intend to imply that this perspective will reflect the views of all prisoners, but it does reflect the views of many prisoners we have heard from who have experienced one to two months of cell confinement quarantine and/or isolation. The ultimate lesson that society as a whole may learn from this pandemic is that a one-size-fits all protocol is not necessarily effective for all demographics, and may cause additional harm for some demographics, most especially in a prison environment where there are cultural, logistical, and architectural barriers to the sorts of public health protocols that may work well enough in other settings.

I write these words from a cell in quarantine, my second time here in the last five six weeks or so. In between stays I was confined to my cell on my housing unit, which has been locked down for over a month now. It is easy to dismiss as a trifling matter the confinement of a human being, for over a month and counting, to a concrete box—unless you happen to be one of the human beings so confined. The day-to-day grind of life when you’re stuck in such a situation takes a toll on the physical and mental health of the best of us, in ways too subtle to properly convey. Suffice it to say that the hardship is real, it is immediate, and presently it is being inflicted upon hundreds of prisoners across the state (quite apart from those made to languish in solitary confinement as a matter of course, even under “normal” circumstances—but that is a subject for another time).

Much of what led to this mess—and no mistake, this is a capital mess—is what also led to the confusing, inconsistent, terribly harmful situation affecting those in society: the decision on the part of many to imbibe the fear poured on a daily basis by ambitious politicians and their shills in the media; a near-universal failure to soberly assess the data, while, with a straight face, telling others to “follow the science”; and an ignorance of the damage wrought by measures intended—ostensibly, anyway—to alleviate suffering.

There exists an added element to the situation in here, however; it is that many of the harmful things done by prison officials this past year were done at the behest of public health agencies and members of the public who meant well, but who were largely driven by fear. At some point it becomes necessary to critically examine the actual threat posed by the corona virus, the real data concerning its potential for harm, and what the wisest course of action is at the present time. This examination should be free of political and social biases, which hitherto have plagued nearly every facet of the pandemic.

It is almost a certainty that such an objective analysis would result in the realization that we failed to properly judge the corona virus, or to really even consider what harm we might be causing in the efforts to fight it (incidentally, this “fight” against yet another unseen foe, led by slick, pretentious, politicians drawn to the limelight like moths to a flame, is redolent of the “wars” against drugs and terror—neither of which turned out very well).

We would never consider for a moment disrupting our lives—some might say nearly ruining—as we have done for nearly a year now, on account of the flu. Yet an objective, meaningful assessment of the present situation leads one to the conclusion that, if the corona virus is in fact deadlier than the flu—something difficult to ascertain because of the tallying as COVID-related those deaths resulting from other causes, including the flu—it is not deadlier by far.

In any case, the facts certainly do not warrant the hysteria on which many of us have seemingly thrived for the past several months, and it is precisely this hysteria that lies at the heart of the situation in which we find ourselves at present (and we are all in it, though I think I may be forgiven for pointing out that some of us are a little deeper in it).

Much of what resulted would have likely occurred anyway, and none of the preceding should be construed as stating that public health officials and advocates are responsible for the present plight of prisoners. Such an assertion would be manifestly unfair. However, it is probably true that a good deal of the pressure placed on the DOC by public health officials and advocates to do something, anything, has had unintended consequences which perhaps should have been foreseen.

Almost invariably the DOC’s approach isn’t to do something meaningful, but rather to give the appearance of doing something meaningful. Its handling of the pandemic has been no exception. Many of the measures taken by prison officials may look good on paper, but then so do Communism and the Correctional Industries mainline menu. The reality has been quite different for prisoners. This reality has included, among many other ridiculous things too numerous to list: (1) Having limited access to outdoor exercise, even during those periods this year when we were not lockdown entirely, as we are now seeing; (2) an apoplectic guard who was not wearing a mask scream at inmates to put on their masks, as they were on the phone talking with friends and family; (3) being taken to quarantine the day before one’s scheduled wedding because one’s cellmate—gasp!—happened to walk by another inmate who was not infected but lived on a unit with several positive cases; (4) not seeing or touching your loved ones for nearly a year, even though staff members have been permitted to enter these facilities, interact with prisoners for eight hours, leave, and come back the next day to repeat the process (I don’t have children, but I can imagine how difficult it must be to not see one’s kids for an entire year, or how hard it is for the parent or guardian in the free world to explain to the child why s/he cannot see mom or dad for what must seem like ages; (5) having your unit locked down for over a month, during which time meals are hours late because medical staff members are going door to door taking the pulses, every day, of all the inmates—even those who are young, healthy, experiencing no symptoms, and who’ve tested negative several times in previous weeks; (6) showering and making phone calls just once or twice a week; (7) high blood pressure, anxiety, heart palpitations, and any number of other ailments concomitant—depending on the individual and her or his disposition—to living in a box 24 hours a day; (8) having medical staff sweep to the side various non-COVID health issues because management has taken the position that COVID prevention (an impossibility) and treatment (nearly an impossibility, considering the nature of our captors) are paramount etc., ad nauseam.

It’s worth noting, by the way, that the idea of confining hundreds of individuals to a building with a communal ventilation system, preventing them from going outdoors for fresh air and exercise, and encouraging poor hygiene by limiting showers to just once or twice a week, well, to say it’s myopic would be to lend it credit it hardly deserves. It was madness when it was suggested, it was madness when it was implemented, and it is madness now, as I write these words from my stuffy concrete box in quarantine.

It is probable that one or two or 10 readers will opine to themselves “Well, I’m sure he’d change his tune if he were to contract the virus” (there is a spiteful creature in every bunch, and this pandemic has hardly brought out the best in us). The screwy “logic” of this sentiment aside, what I will say is that I have contracted it. I write the above having been told several days ago that I tested positive. Curiously, I’d gone all year without contracting it (at least to my knowledge), and it wasn’t until I’d been confined to my cell for over a month of quarantine—and tested negative five times in that period—that I got it. So did 50 other people on my unit alone. So much for the preventive measures of the DOC.

In closing, I think it’s important to stress the need for assessing things in a practical manner and determining a course of action not on how we think things should work, but the way we know—from our experiences in dealing with these nocuous bureaucrats—how they will actually work. It is rarely a good idea to make decisions based on fear, or to induce others into making such decisions. But this is precisely what many of us have done since COVID-19 entered our lives early this year, and we don’t seem to have learned too many lessons from the mistakes that should be obvious to us all. We should learn from our mistakes, and remember that we needn’t remain tied to them. This pandemic will eventually be a thing of the past. In the meantime, let us exercise care so that we don’t cause harm in its name.

-Joey Pedersen, Washington State Penitentiary, December 2020

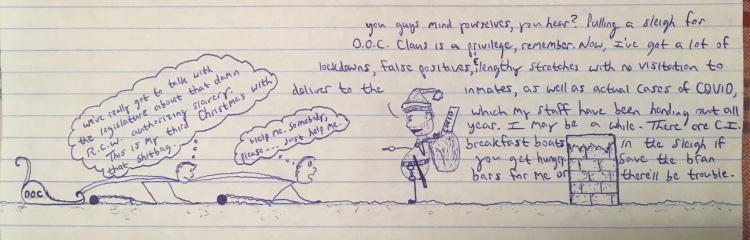

WA DOC Prison Labor Model Amplifies COVID-19 Vectors & Outbreaks

On December 15, 2020, a Washington State Penitentiary (WSP) associate superintendent told families of WSP prisoners during a COVID-19 Local Family Council informational Microsoft Teams meeting that WSP leadership has not been authorized by the WA DOC headquarters Unified Command to make exceptions during the pandemic to policies that punish prisoners with major infractions if they refuse to work. (See WAC 137-25-030, Violation 557 – Refusing to participate in an available work, training, education, or other mandatory programming assignment.) At least some prisoners who are currently on quarantine lockdown at WSP are being asked to leave their cells and potentially expose themselves or others to COVID-19 by carrying out regular assigned job duties, to include serving food to other prisoners on quarantine lockdown. Reportedly, some prisoners are being asked to work far more hours per day than would be their usual assignment—up to ten hours a day in some cases.

When families expressed concern during the meeting about DOC knowingly creating new COVID vectors by having prisoners who are supposed to be in quarantine lockdown leave their quarantine cells to physically move around in areas that will create two-way exposure to other prisoners and staff members, the associate superintendent had the following things to say:

It is a policy. If they receive an assignment, and they refuse, it is policy. We rely on the incarcerated population to help us with that work. We are hemorrhaging staff. We are responsible to make sure that incarcerated individuals eat. How do you suggest that we make sure everyone eats? It is the expectation of anyone who supervises me for me to uphold policy. We are reliant on incarcerated individuals to help us work. There’s no two ways about it.

When asked how the prison staff members are faring during all of this, the associate superintendent conceded that he, all of his staff members, and all of the prisoners with whom they work feel tired, tense, and strained. Clearly, something about mass incarceration in Washington state and/or WA DOC emergency preparedness plans appears not to be working. As this blog post is being written, over fifty new positive COVID cases in WSP’s medium security quarantine lockdown units are sending prisoners packing up their boxes tonight to move to isolation units. Interestingly, in cases where a prisoner has tested positive and his cellie has not, WSP appears to be considering assigning new prisoners as roommates to the cellie who is left behind, knowing full well that the cellie has been living with someone who has now tested positive. The prison labor model may not be the only COVID vector WA DOC is knowingly creating.

Here is what Joey Pedersen, a prisoner who has spent over a month in quarantine lockdown at WSP, has to say about WA DOC’s labor model and COVID-19:

One of the many sordid aspects of the DOC’s response to COVID-19 is that DOC has, in numerous instances, infracted prisoners for refusing to work. In other words, while on the one hand claiming that the pandemic is so serious that visitation must be shut down for a year, outdoor exercise drastically curtailed, hundreds of prisoners tossed into solitary confinement (often without so much as a book to read), and entire units placed on lockdown so that inmates are afforded opportunities to shower and use the telephone just a couple times each week (if they’re lucky), prison officials are, on the other hand, requiring prisoners to come out of their cells and work around others, often for upwards of 10 hours each day. For sheer effrontery, it’s difficult to surpass this.

It’s worth noting a couple of things here. One of them is that it is probably true that the majority of prisoners are not concerned about COVID, believing that, while it is highly contagious and can–in relatively few cases–prove fatal, it is not as serious as the media have led us to believe, and the DOC’s response to the pandemic has been terribly inconsistent and has caused more harm than good. Not all prisoners feel this way, of course, but from all the information I have personally gathered this past year, it is probable that far more inmates believe this than disbelieve it.* The validity of such a position is not important here. What’s important is the frustration on the part of the prisoners who feel as though their captors have used the pandemic as a pretext for taking what few privileges and rights were left them in the first place.

Another thing that needs to be made clear is that what the DOC is perpetuating when it compels prisoners to work, using various means, is slavery. We can call it by whatever name we like. It’s slavery all the same, pretty dress or no. The 13th Amendment to the US Constitution makes slavery in prisons legal, and the Washington State Legislature—through both inaction and the creation of RCW 72.60.110—has failed to establish a more humane and ethical standard for Washington state.

If as a society we are going to condone slavery, we should summon whatever decency may be left us and at least acknowledge that’s what we’re doing. We may say it’s justified because the slave robbed or killed someone, sold illicit substances, or whatever the case may be, but that slope is awfully slippery; whatever the case, we should call it what it is, just as the lawmakers who authorized it should have called it by its name.

What makes the present situation so troubling is that the DOC isn’t simply forcing inmates to work; it is forcing them to work in what prison officials claim is an environment so dangerous that entire units must be locked down. They are causing inmates to expose themselves to a virus that their official line claims is running rampant throughout the prison population. If the DOC is to maintain any credibility whatsoever with the public–something many of us do not believe possible–it must alter an unconscionable stance that simply cannot be defended.

If any good may come from this contretemps, let it be this: light is cast on the practice of modern American slavery, a vestige of a shameful past that our legislators should no longer be permitted to ignore.

* Viewed objectively, it is difficult to maintain the media line when one considers that, if COIVD were half as serious as it’s been made out to be, these facilities would long ago have been ravaged. They’re essentially sardine tins, and it’s not a question of “if” but “when” prisoners will get exposed to COVID. Nearly a year into the pandemic we have seen relatively few deaths among the prison population (low single digits), which data–even if accepted at face value–simply do not comport with the hysterical position of the media and government. This is why the majority of inmates are not overly concerned about COVID. This does not in any way minimize the fact that there is a highly contagious virus that can prove fatal in older and less healthy individuals. It’s simply a sober assessment of the data.

Another Documented Case of Retaliation in WA DOC

The Office of Corrections Ombuds recently found and reported on evidence of retaliation at WA DOC’s Reynolds Work Release site. WA DOC has provided a response here, in which it states that “‘Retaliation’ is not in alignment with the Department’s values. The Department is incorporating the definition of the term ‘retaliation’ as well as examples into annual required training by all corrections staff. Assistant Secretary Armbruster will be meeting with all work release supervisors to discuss ‘retaliation’ and stress the importance of zero tolerance of retaliation within work release facilities.”

In this post, we look at what is known about retaliation in WA DOC and what a person might do to mitigate it.

Retaliation and Efforts That Backfire

- Regardless of what supervisory staff may say, retaliation occurs in WA DOC, just as it occurs in all large organizations. (See documented examples of retaliation in WA DOC here.) Retaliation happens between coworkers in WA DOC, between staff and prisoners, between staff and prisoner’s visitors, and between prisoners and other prisoners. Retaliation can occur because someone felt slighted, humiliated, undervalued, or tattled on. Retaliation is hard to prove because it often takes the form of someone behaving in a way that is technically allowed by policy, but that is markedly imbalanced or biased in how it is applied, or is radically different from previous ways of behaving. It is typically cumulative, which is to say that many small policy-approved behaviors accumulate over time to intimidate, harass, remove, or “build a case” on someone. Using policy-approved behaviors in an excessively frequent or bullying manner is undeniably retaliation, but few WA DOC supervisory staff are willing to openly acknowledge this.

- Sometimes retaliation is inevitable when raising a complaint with WA DOC staff and supervisors. Weighing the pros and cons leads many to avoid raising complaints, since precious things can be irretrievably lost when retaliation is severe, and when the impossibility of proving it precludes any sort of justice or corrective action. However, if we are all too paralyzed by fear of retaliation to act, we become complicit in condoning the very culture that harms us. It’s a tough balance to strike, especially in situations where individuals are stuck living, working, or visiting in one small prison community for a very long time. If retaliation does occur, it is difficult to determine if supervisors are taking it seriously. As previously stated, most staff disciplinary actions happen quietly, out of view from the aggrieved, and protections written into union collective bargaining agreements (PDF pg. 25) and prisoner grievance manuals (PDF pg. 12) ensure that most staff disciplinary records are kept sealed or are expunged after one year, if they are recorded at all.

- Risk of retaliation can sometimes be reduced (but also can sometimes be exacerbated) by some of the following methods—if nothing else, these methods at least leave a more public paper trail when documenting retaliation:

- CC’ing a supervisor or outside official (such as a legislator, union representative, attorney, or ombuds) in email communications with staff.

- Requesting that a staff person from WA DOC headquarters come to a local prison facility to meet with you and a local facility staff person to resolve an issue.

- Bringing in an outside conflict resolution expert.

WA DOC COVID-19 Response

For those wanting updates on DOC’s Corona virus response, here is DOC’s official (and evidently regularly updated) response info, as well as the Office of Corrections Ombuds COVID-19 resource page, which contains notes from a group phone meeting held with concerned families of prisoners on March 13, 2020. This WA Corrections Watch post was last updated on March 14, 2020 at 1:18 PM.

Things families and supporters have been hearing from prisoners at Monroe Correctional Complex:

- No systematic protocols for screening staff have been developed.

- Hand sanitizer, bleach, and many other virus-combating hygiene and cleaning supplies are considered contraband and are therefore not allowed in the possession of prisoners.

- At least one staff person is reported to believe that Coronavirus is a hoax meant to damage President Trump’s political future.

- At the WSRU unit prisoners from a quarantined unit are reported to have been allowed to have contact with prisoners from a non-quarantined unit.

- Prisoners say staff are not being told that they can receive compensation if they need to take more than the usual approved leave for illness.

- College programs and visits from prisoners’ families have been cancelled until further notice.

- At least one prisoner is reported to have been held past release date in facilities imposing quarantine lockdowns.

- There are concerns about insufficient prisoner access to immune-boosting nutrients and healthy, whole foods in WA DOC prisons.

A UW PhD candidate who has a loved one in the WA DOC system has created this form letter template for people to use when contacting legislators, the Governor’s office, DOH, etc. about Corona Virus response concerns:

Dear XXX,

On March 13, 2020 all prisoners at the Washington State Reformatory Unit in Monroe received notification that a guard who works on the A&B side of the prison tested positive for COVID19. According to the letter sent to prisoners the guard was last in the prison on March 8th. The letter to the prisoners was dated for March 12th and passed out on the morning of the 13th. A&B side will be locked down until March 22nd.Bleach and alcohol based hand sanitizers are considered contraband in the prison. Only porters are authorized to use bleach. The only cleaning supply provided is an “all purpose cleaner” that is so mild it is safe to drink. The prison is not providing people with extra rags or cleaning supplies. The DOC has told prisoners to put socks on the public pay phones to protect themselves from shared germs.There are currently upwards of 1,400 people 60 years and older incarcerated in Washington State.Given the deplorable history of medical care at Monroe (and in prison in general) it’s important that legislators such as yourself are prepared to hold DOC accountable and ensure they are providing incarcerated people with proper medical care. Here are some suggestions:

- Make alcohol based hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes, cleaning rags, latex gloves, surgical masks (for those who are sick) etc available for free and NOT considered contraband

- Establish a quarantine location that is not in the living units and is NOT solitary confinement

- Prepare the hospital with necessary medical equipment such as ventilators

- Prepare to transfer those who are high risk into free world medical care

- Have additional trained medical staff who are not DOC work with the DOC to treat patients

- Enable the calling function on incarcerated people’s JPay tablets so that they do not need to use public phones (as of now, they’re putting up signs telling folks to put a sock over the phone if they need to)

- Set clear limitations on the use of solitary during this time

- Set clear limitations on the overuse of lock down during this time

- Test all guards and staff who enter the prison

- Make tests widely available

This is a crisis. There are tens of thousands of vulnerable people locked up and in the state’s care. Something needs to be done immediately.

Thank you,

A prisoner at MCC just sent me this on JPay: “Apparently this coming week is Sunshine Week, and TVW is highlighting what the Public Records Act means to Washingtonians.” Perhaps in honor of Sunshine Week (my new favorite week! I had no idea it existed…) we could all make some public records requests from DOC, perhaps pertaining to its Corona Virus response or its work with Vera Institute on solitary confinement reform? Or any other endless number of topics of concern… For anyone who has never tried doing this, here’s a guide.

Lobby Day 2020

Please join the Washington Coalition for Prison Reform and Prison Voice Washington for lobbying efforts and an evening rally to end mass incarceration on Monday January 20th. More information here.

Meeting With a State Legislator on Lobby Day? Quiz Them on WA DOC Leadership Expertise

Lobby Day is coming up on MLK Jr. Day and many constituents who would like to see reforms in WA DOC will be meeting with their legislators. It helps to have some key talking points planned out to make the best use of the brief appointments one might make with a Washington State senator or representative. We’ve put together an analysis of historical and current WA DOC expertise to give constituents some additional concrete details for their talking points. Happy lobbying!

When (and Why) Did WA DOC Prisoners Lose the Right to Wear Personal Clothing?

As documented in Greenhalgh v. Dep’t of Corr. (2014), WA DOC eliminated the right of prisoners to wear personal clothing in 2009. (See also DOC 440.000 and these early revisions of WA DOC 440.050 State-Issued Clothing/Linen.) As this Court of Appeals decisions states:

“In January 2009, DOC informed its inmates that it amended DOC 440.000 to eliminate inmate possession of excess or unauthorized personal clothing items by January 2010. Inmates had the following disposition options: (1) between July 1, 2009 and September 30, 2009, inmates could send out the clothing at DOC’s expense; (2) through December 31, 2009, inmates could give the clothing to a visitor; or (3) after December 31, 2009, inmates had 30 days to dispose of excess or unauthorized clothing. If an inmate was indigent, refused to pay postage, or failed to designate someone to receive the clothing, DOC donated or destroyed it. After January 1, 2010, all unauthorized personal clothing became contraband.”

All this after WA DOC promised hunger-striking prisoners at Washington State Penitentiary in 1999 that personal clothing would not be taken away. Was there a reason after so many decades that WA DOC staff suddenly couldn’t tell prisoners apart from non-prisoners and had no choice but to make this change? Or was this a chance for Correctional Industries to deepen their monopoly on captive consumers? Does having prisoners wear designated clothing make staff more or less vigilant about keeping track of where prisoners are and are supposed to be? Your guesses are as good as ours…

The Report Cards WA DOC Gives Itself

How would those who live, visit, and work at WA DOC prisons rate those facilities? And how would that compare to WA DOC headquarters report card ratings? Try your hand at it. Think of a WA DOC facility. Give it a grade in all of the following areas: (1) operations review (IT, security, disciplinary processes, food services, “offender” management, secured housing, searches & evidence, staff safety & accountability) and (2) health services (general, infirmary, medications, health records, restricted housing). Now compare your grades to WA DOC’s grades, which it reports in its facility-specific Operations Review Reports…