While some sections of this page are primarily designed to help “free world” civilians communicate with WA DOC, we suspect that much of this page could be helpful to WA DOC staff as well. None of the guidance provided on this page should be misconstrued as legal advice. Please see our list of legal resources if legal help is needed. If there are ways in which we could improve on the guidelines we provide here, please contact us and let us know.

- Understanding Paramilitary Culture, Staff Rank Titles, and the Chain of Command

- Locating Staff Workplace Contact Information

- Strategies for Effective Communication and Resolution

- Template for Emailing WA DOC Staff & Supervisors

- Expectations for Responsiveness

- Retaliation and Efforts That Backfire

Understanding Paramilitary Culture, Staff Rank Titles, and the Chain of Command

- The comportment of WA DOC staff can be disconcertingly gruff for civilians who are unaccustomed to WA DOC prisons. WA DOC employees are trained using uni-disciplinary curricula that emphasize short-term custody and security issues above—and at the expense of—all else. These curricula pound the message into staff that prisoners are manipulative, that prisoners’ families are vectors of contraband, and that dehumanizing, exaggerated distance must be kept to prevent staff from becoming compromised. Lessons on pro-social interpersonal skills are largely absent from WA DOC training curricula. Thus, there are few consequences for WA DOC employees who interact with prisoners, coworkers, visitors, and even legislative or judicial guests in a manner that is gruff, apathetic, or downright rude. WA DOC curricula have yet to emphasize multidisciplinary skills and long-term public safety strategies of modeling pro-social behavior. However, the cultural reform goals in WA DOC’s 2019–2023 Strategic Plan and the rumor that new training curricula are being developed tempt us to get our hopes up. All this said, sometimes the custody employees who seem gruffest on the surface will reveal good hearts and fairness in the moments that truly matter. Be wary, but also don’t be too quick to jump to conclusions. Prison employees have their own complex life experiences and they are sometimes assigned to work in highly unpleasant environments doing monotonous or stressful tasks. Many WA DOC employees are military veterans, some of whom have experienced active combat zones. Observe how they interact with all stakeholders in the prison to get a better feel for who they are.

- WA DOC has two primary types of local facility prison staff: custody uniformed staff and program/administrative staff who wear civilian clothes. Ranks are as follows, from lowest rank to highest rank:

- Custody: Correctional Officer (C.O.), Sergeant, Lieutenant, Captain

- Program/Administrative: clerical staff, counselors (case managers), Custody Unit Supervisors, Correctional Program Managers

- Above both categories are the Associate Superintendents and the facility Superintendent. See the prison facility organizational charts to learn the names of local leadership staff.

- WA DOC headquarters has an Executive Strategy Team and Prisons Division leadership that rank above local facility staff. These headquarters leadership staff members may come from either a custody or a program/administrative background, and typically have decades of experience in corrections. Headquarters staff rank, starting with the highest rank, is as follows: Secretary, Deputy Secretary, Assistant Secretary, Director, Deputy Director

- See the Prisons Division organizational chart to learn the names of headquarters leadership staff and the more nuanced details of headquarters staff rank and jurisdiction

- Headquarters also has additional divisions with their own organizational charts. See here for a complete list.

- Seniority and rank matter a lot to WA DOC staff, as does maintaining control of narratives about events. While jumping the chain of command with a complaint can sometimes ensure or accelerate resolution of an issue, it will also ruffle the feathers of lower ranking staff. The long-term consequences for brazenly jumping the chain of command may be passive stonewalling of future requests or overt retaliation. The benefits may be a slight improvement in certain systemic problems due to the pressure of supervisory or outside scrutiny.

- Promotions do not happen on the same timeline for all prison employees. Some custody employees might work as corrections officers for decades without much in the way of promotion, while others climb the ladder more rapidly. In supervisory dynamics, seniority can sometimes informally trump rank. For example, a relatively young sergeant is unlikely to be overly assertive when tasked with supervising a cantankerous elderly corrections officer who has held the C.O. position for decades. One needs to understand this when seeking assistance from a young supervisor for issues with a subordinate staff member with more seniority.

- Loyalty to coworkers matters a lot in WA DOC. There is great pride in correctional culture, and WA DOC employees often work with the same coworkers for decades, spending a lot of time with each other in the community outside of work. It is common for spouses and family members to work together at the same prison and even in the same post, sometimes for multiple generations. Loyalty to coworkers often takes the form of upholding a coworker’s decision, even when it is questionable, and even when the coworker is a subordinate. Backing up a coworker is perceived as an important tool of safety and security. Showing disagreement with or questioning a coworker in front of prisoners or free world visitors is seen as showing weaknesses or cracks in staff control over the prison environment. Resolution of problems can therefore be hard to come by, and when it does happen, prison employees are unlikely to acknowledge it directly. Most staff disciplinary actions happen quietly, out of view from the aggrieved, and protections written into union collective bargaining agreements (PDF pg. 25) and prisoner grievance manuals (PDF pg. 12) ensure that most staff disciplinary records are kept sealed or are expunged after one year, if they are recorded at all.

Locating Staff Contact Information

- Tracking down WA DOC staff workplace contact information can be extremely challenging. WA DOC provides no comprehensive staff directories on its website. Supervisory staff have business cards if requested, but typically one’s only option for communications by telephone entail calling the main prison phone number and then being endlessly transferred or put on hold. (Local prison facility contact information is here.) Leaving a voicemail rarely results in a returned phone call. Thus, it can help to also use email communications.

- To email WA DOC staff, one needs to know a correctly spelled first and last name. This list of Washington State employee salaries is often the most helpful way to locate that information (for Agency, check “Corrections”). WA DOC email addresses usually follow consistent patterns, except for variations used to disambiguate email addresses for employees with identical names or initials. Every WA DOC employee has two forms of their email address: FirstName.LastName@doc.wa.gov or FirstInitialMiddleInitialLastName@doc1.wa.gov (for example, WA DOC Assistant Secretary Robert L. Herzog can be reached at Robert.Herzog@doc.wa.gov or at RLHerzog@doc1.wa.gov).

Strategies for Effective Communication and Resolution

- Maintain civility and professionalism.

- Be clear and concise, and provide specific details about time and location of incidents.

- Pick your battles wisely.

- If you know you are not skilled at writing, or if you lack experience with WA DOC or framing arguments, try to have someone more knowledgeable check your draft for typos, spelling/grammatical errors, logical flaws, missed opportunities to make a systemic argument, etc. before you send it. The more ignorant you appear, the less seriously WA DOC will take you, and the less obligated they will feel to go out of their way to find win-win solutions. Consider using our Template for Emailing WA DOC Staff & Supervisors if you need help wording and structuring your communications.

- Document everything, including notes from phone calls with staff, in emails to staff so there is always a date-and-time-stamped record of events and patterns over time (keeping in mind that emails to WA DOC can be public disclosed by anyone in the public).

- If you have an incarcerated loved one, consult them before communicating with staff and come up with an agreed upon plan for communicating.

- Maintain dignity, avoid Stockholm Syndrome. You are less powerless than you think, though you must also educate yourself about WA DOC to avoid making missteps and to compensate for your powerlessness.

- If meeting or collaborating with staff or supervisors to address issues of concern, be mindful not to undermine the well-being of others by making unnecessary long-term concessions for personal short-term gain. The things you concede or endorse with WA DOC in your own situation may be misused to legitimize certain harmful approaches on a systemic level. (For example, many prisoners’ families advocate individually with WA DOC staff for the right to buy better quality mattresses for incarcerated loved ones. The risk here is that if this is granted, mattresses could eventually become yet another expense of incarceration that is shifted from the state to financially-depleted families of prisoners.)

- Use language from WA DOC’s own policies, mission statement, and strategic plan to strengthen how you frame your presentation of a concern. Show WA DOC how your individual case demonstrates broader systemic trends or concerns.

- Pros and cons of phone calls or meetings with WA DOC staff: WA DOC employees may reveal more information during phone calls or meetings than in emails, but keep in mind that when a DOC staff person requests a phone call or a meeting, it is likely in part because they don’t want to create a disclosable public record or formal documentation of a concerning pattern.

Expectations for Responsiveness

- Expect that…

- Communicating with WA DOC will be unlike any other communication experience you have ever had. Whatever communications etiquette or protocols you may be accustomed to from interacting with other agencies, businesses, or people are expectations you should probably just abandon at the door. Prepare to be frustrated, blindsided, partially helped, sometimes worse off than you were before you made the effort, or sometimes pleasantly surprised.

- Two out of ten WA DOC staff members will be prompt, helpful, and highly responsive to inquiries or requests for assistance. Three out of ten will take at least two to five business days to respond. An additional two out of ten will completely ignore you until you get a supervisor, attorney, or legislator in on the email chain, and will then only respond to you with a curt, one- or two-line email. Still two others will refuse to respond directly to you, but will at least refer you to the infuriatingly generic and alienating WA DOC Correspondence Unit, which will give you some form or another of the classic runaround. The remaining one out of ten will either be on vacation (get used to out-of-office auto responses) or will email you back and ask you to call them, perhaps for reasons we have already speculated.

- Local facility superintendents at some WA DOC prisons are highly unresponsive, while “sups” at other facilities can be the most responsive of staff. Luck of the draw… They are legitimately busy, but some are quite apathetic about engaging anyone they don’t perceive as directly contributing to their immediate custody objectives. (What’s that about can’t see the forest for the trees?)

- A follow-up inquiry that’s sent too soon will only further reduce the chances of receiving a meaningful response. If the issue isn’t an emergency, allow several business days before following up.

Retaliation and Efforts That Backfire

- Regardless of what supervisory staff may say, retaliation occurs in WA DOC, just as it occurs in all large organizations. (See documented examples of retaliation in WA DOC here.) Retaliation happens between coworkers in WA DOC, between staff and prisoners, between staff and prisoner’s visitors, and between prisoners and other prisoners. Retaliation can occur because someone felt slighted, humiliated, undervalued, or tattled on. Retaliation is hard to prove because it often takes the form of someone behaving in a way that is technically allowed by policy, but that is markedly imbalanced or biased in how it is applied, or is radically different from previous ways of behaving. It is typically cumulative, which is to say that many small policy-approved behaviors accumulate over time to intimidate, harass, remove, or “build a case” on someone. Using policy-approved behaviors in an excessively frequent or bullying manner is undeniably retaliation, but few WA DOC employee supervisors are willing to openly acknowledge this.

- Sometimes retaliation is inevitable when raising a complaint with WA DOC staff and supervisors. Weighing the pros and cons leads many to avoid raising complaints, since precious things can be irretrievably lost when retaliation is severe, and when the impossibility of proving it precludes any sort of justice or corrective action. However, if we are all too paralyzed by fear of retaliation to act, we become complicit in condoning the very culture that harms us. It’s a tough balance to strike, especially in situations where individuals are stuck living, working, or visiting in one small prison community for a very long time. If retaliation does occur, it is difficult to determine if supervisors are taking it seriously. As previously stated, most staff disciplinary actions happen quietly, out of view from the aggrieved, and protections written into union collective bargaining agreements (PDF pg. 25) and prisoner grievance manuals (PDF pg. 12) ensure that most staff disciplinary records are kept sealed or are expunged after one year, if they are recorded at all.

- Risk of retaliation can sometimes be reduced (but also can sometimes be exacerbated) by some of the following methods—if nothing else, these methods at least leave a more public paper trail when documenting retaliation:

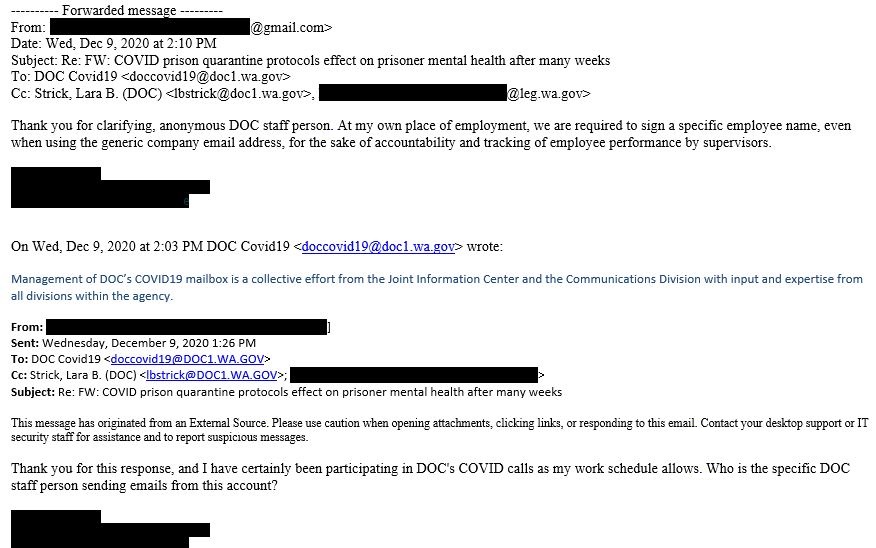

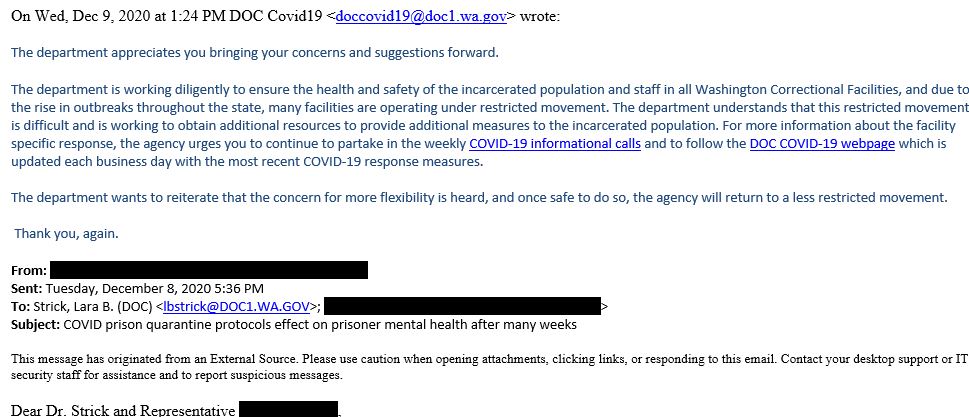

- CC’ing a supervisor or outside official (such as a legislator, union representative, attorney, or ombuds) in email communications with staff.

- Requesting that a staff person from WA DOC headquarters come to a local prison facility to meet with you and a local facility staff person to resolve an issue.

- Bringing in an outside conflict resolution expert.